The Munsons of Texas — an American Saga

Chapter Twenty-one

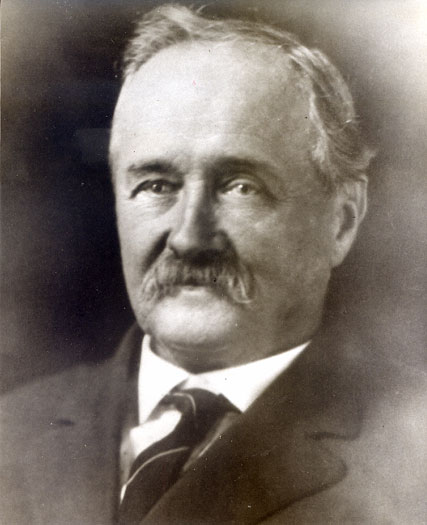

THE LIFE AND FAMILY OF HENRY WILLIAM MUNSON III

b. 1851 — d. 1924

SUMMARY

Mordello and Sarah Munson’s first child was born on August 16, 1851, and was named Henry William Munson. He is considered to be Henry William Munson III. He grew up on Ridgely Plantation at Bailey’s Prairie. Being a child of the Civil War and Reconstruction years, he attended Texas Military Institute in Austin and then took military training at the newly opened Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas near Bryan. In the early 1870s he became captain of the Prairie Rangers of Brazoria County. At the age of 45 he married Sarah Kate Cahill, and they had one son, Joseph Waddy Munson II. Kate died in childbirth a few years later and Henry William never remarried. Joseph Waddy II grew up in Angleton and married Myrtle Bryan. Of their two children, Bryan and Jennie Kate, only Jennie Kate married and has descendants to carry on this branch of the Munson family.

Henry William Munson III

Mordello S. Munson and Sarah K. Armour were married on February 6, 1850, and moved into the “Russell Place" at Bailey’s Prairie. They named this home Hard Castle. Their first child was born on August 16, 1851, and records show that he was born at “the old home place near Peach Point.” This indicates that Sarah went to Oakland Plantation to be with Mordello’s mother, Ann, for the birth of her first child. Rather appropriately, being born at Oakland Plantation, he was named Henry William Munson. In his mother’s letters in later years, he was always referred to as “Son,” and a half-century later, when he was a widower and the loved and honored eldest member of the family, he was always called “Uncle" by members of the family. Today his few remaining elderly nieces always refer to him, very naturally and simply, as “Uncle.”

Henry William grew up at Ridgely Plantation, his first fourteen years during slavery times. This was the only social system his family had known for over three generations. He was eleven when his father left for the Civil War and fourteen when the war ended. This, together with his experiences during the difficult Reconstruction years, undoubtedly had a strong influence on his views for the rest of his life.

Henry William Munson III was a tall, handsome man of fine physique, and like all his brothers he became an expert cattleman, horseman, rifleman, and hunter. There were no fences on the ranch lands and the cattle ran loose, and a necessary duty during the boys’ younger years was to “go hunting" and “bring in the beeves" for food for the family. They also brought home deer, squirrels, ducks, and geese; and they hunted bobcats, possums, raccoons, and armadillos in the woods.

Early Texas A&M College

After his home education at Bailey’s Prairie, Henry William

attended public schools in Houston and the Texas Military Institute

in Austin (moved from Bastrop to Austin in 1870), where his father

was a member of the state legislature. He then attended the

recently opened Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas at

College Station for special military training. Texas A. & M.

had opened its doors for students, after strong leadership support

by Mordello Munson and John Adriance in the state legislature, on

October 4, 1876, with an initial class of forty students and a

faculty of six ![]() . As Henry William was 25

years old at that time, he very likely may have been a member of

that first class. After completion of his training there, he

returned to Bailey’s Prairie and lived “at home,” helping his

father operate the plantation.

. As Henry William was 25

years old at that time, he very likely may have been a member of

that first class. After completion of his training there, he

returned to Bailey’s Prairie and lived “at home,” helping his

father operate the plantation.

Henry William spent much time during these years traveling back and forth between Texas and Tampico and Tuxpan, Mexico, by ship. Being single and free to do so, he was the overseer of the Tuxpan sugar plantation and mill, which operated under a local manager. During many of these years he was the only adult son who was not married or in school, and he apparently acted as his father’s partner and manager. He continued to pay taxes on the Mexican property for many years, but after his death it was abandoned and eventually was taken by the Mexican government.

The following is a quote from his obituary in the Angleton Times in 1924:

Back in the early seventies, Mr. Munson had much to do with the organization of the Prairie Rangers, and was made Captain. This organization operated under the authority of Governor O. M. Roberts. Its purpose was to control a lawless element that was present in the county at that time. A criminal class of Negroes made cattle stealing a regular practice, defying all law, and boasting of their raids. The Prairie Rangers put fear into their hearts and forced respect for law.

It is reported by his nieces that Henry William was “quite a ladies’ man,” but he did not marry until the age of 45. He once aspired to marry Miss Terease Bryan of the prominent Bryan family, but a letter from him to his mother tells that she had decided to marry another man. An entry in Sarah’s diary dated July 12, 1882 (just fifteen days after her daughter Emma’s wedding to the Reverend Joseph Murray) states: “Poor son in deep trouble from the doing of an artful and heartless woman whom he had learned to love and trust. May God in his goodness protect him from falling into the snares of such again and bless him yet with a wife, worthy of so noble and confiding a heart is the prayer of his loving Mother.” An entry five days later reports, “Son lingered behind to see about a reconciliation,” and on July 25: “Son, his Papa and I talked until twelve. He is at last free from. . .woman pronounced by her own father a ‘heartless flirt’ and a girl full of deception. I read a very kind sympathetic letter from Mrs. Jimmie Perry to son, she says she could not have believed `one she thought so pure and noble would have proved so false and fickle.’ I hope our over ruling Providence is directing him and pray He will lead him in paths of pleasantness and Peace. Rec’d a letter from Emma. She will be home soon.”

Soon thereafter, possibly as a result of this disappointment, and at about the age of 31, Henry William moved with his brother George and family to live at the “Van Place" north of Bailey’s Prairie. After this, Henry William and brother George were lifelong partners, engaging in cattle ranching, rice farming, and other endeavors as “H. W. and G. C. Munson.”

Henry William was married at the age of 45 to 20-year-old Sarah Kate Cahill at her home near Chenango, Texas, on December 18, 1896. Kate’s father, Mr. J. J. Cahill, was manager of the Chenango Plantation which lay just to the east of the “Van Place" and adjoined the Kennedys’ Waverly Plantation. It was common practice for young men and ladies from neighboring plantations to marry, with the girls often being quite young. All of Henry William’s brothers and sisters except Milam Stephen had previously married.

No information is known about the Cahill ancestry. They had come to Texas from Louisiana. Kate had two sisters, Jennie and Ella, and two brothers, Stephen and Bonny. Ella and Bonny never married. Ella, known as “Aunt Ella" and as “Lollie,” lived all of her adult life with the Munsons as a member of their family, first with Bascom and Addie Munson in San Antonio and later with the Ellen Munson Fowler family in Fort Worth. She died there in about 1970. Stephen Cahill married Leona Barth in 1915, and they raised a prominent family of Cahills, whose descendants live in Angleton today.

Immediately after their wedding, Henry William and Kate made their home at the “Van Place" with George and his large family. Henry and Kate’s first child, a son, was born there on October 3, 1897, and was named Joseph Waddy Munson II for Henry William’s brother. This is one of many cases where early Munson men named their sons for their brothers, a practice which is rare today. Henry William and Kate had two additional sons, both of whom died at birth. The last was born in 1899 at the two-story Angleton home of George C. and Hannah Munson during a great flood, at which time Kate died in childbirth and the baby died a few days later. Henry William and Kate were married less than three years, and Henry William never remarried. Bonny, Jennie, and Mrs. J. J. Cahill may have died soon after the death of Kate, as they are buried beside her and her children in the Munson Cemetery. The cemetery lapsed into a condition of poor upkeep after about 1909 and was little used for the next thirty years. Henry William and his son Waddy moved to Angleton after the death of Kate and first lived with George’s large family in the two-story house on “Munson Row.” He later purchased the second house which brother Bascom had built on "Munson Row,” at what is now 517 Bryan Street. There, engaged in the cattle, rice, and other farming businesses with brother George, he raised his only son with the loving assistance of his large family. Today the older members tell how, in later years, “Uncle" would spend every Sunday — finely dressed — riding his fine horse to visit all of the Munson relatives, and would always come to Sunday dinner at George and Hannah’s house. Following his mother’s leadership, he was always an active member of the local Methodist Church, first in Columbia, then at the Murray Ranch, and finally in Angleton.

Henry William Munson III died on July 1, 1924, at the home of his brother, George C. Munson, at the age of 72, and was buried in the Angleton Cemetery. His granddaughter, Jennie Kate Ankenman, writes: “I was only three, almost four when he died, but I remember him. We lived in Port Arthur and he would take me walking and let me pick flowers out of all the neighbors’ yards. He would also drink my milk (I am told that I hated it - and still do) and brag to Mother that I was such a big girl to drink all of it - not realizing that he had milk on his mustache! Mother says that she couldn’t say a word, because, as far as he was concerned, I could do no wrong.”

His obituary in the Angleton Times reads in part:

The attendance upon the funeral was very large, there being in the gathering an unusually large number of the older citizens from all parts of the county, men and women who knew Mr. Munson in the days of his youth and in his prime, and learned to appreciate to their full value the sterling qualities of his manhood. In the passing of Mr. Munson, Brazoria County loses one more of that band of strong men who guided the county during days that were restless and dark, and brought her through the storms of adversity to her present state of peace and prosperity. To him and others of his class and type we owe a debt of gratitude that never can be repaid. One impressive feature of the burial service was the appearance of five klansmen, robed in spotless white, reverently performing the last sad rites prescribed by the order at the grave of a deceased klansman. This touching service added to the solemnity of the hour.

The Descendants of Henry William Munson III

Joseph Waddy Munson II

Henry William’s only surviving child, Joseph Waddy Munson II, attended school in Angleton, first at the old Albert Sidney Johnston Free School and then at a variety of schools as storms destroyed the fragile school buildings. He graduated from Angleton High School and attended Houston Business College.

On August 22, 1917, at the age of 19, he married Myrtle Bryan, aged 18. Myrtle was born in Damon, Texas on February 14, 1899, the third child and second daughter of Jennie Adell Mock and Joseph Lafette Bryan. She had four sisters and two brothers. Jennie Mock was the granddaughter of John Smith from Virginia, a soldier in the Battles of Velasco and San Jacinto. Waddy and Myrtle first lived in the house on “Munson Row,” now 517 Bryan Street, which his father had bought from Bascom. They sold that house to the Strattons and it later burned.

With the aid of cousin Frank Smith, Waddy took a job with the Texas Company, now Texaco, Inc., in Port Arthur, Texas, where daughter Jennie Kate was born October 12, 1920. Soon thereafter they moved to Houston, where Waddy worked for the Humble Oil Company. Son Bryan Cahill Munson was born there on October 3, 1925. In 1932 Waddy acquired the Humble Oil distributorship in Angleton, and they repurchased their former “Munson Row” lot (now 517 Bryan Street) and built a house there in which they lived until Waddy’s death in 1951. Myrtle continued to live there until she moved to Houston in 1979. Myrtle Bryan Munson passed away December 2, 1993, at age 94, and is buried in the Angleton Cemetery.

Jennie Kate Munson attended Texas Women’s University in Denton, Texas, and the University of Texas at Austin. In 1940 she married Sam L. Leal. Sam Leal had a baby son, Jerry, whose mother had died, and Sam and Jennie Kate had two daughters, Camille, born April 25, 1944, and Carolyn, born June 14, 1946. Sam Leal died in 1955 of a heart attack, and Jennie Kate married Eugene Watson. This marriage ended in divorce after six years, and in 1965 Jennie Kate married Wayne D. Ankenman. Camille Leal is married to John Paul Iglehart, and they have two daughters: Carolyn Ann (Carrie) and Susan Christina (Christie) Iglehart; and Carolyn Leal is not married. Wayne Ankenman died January 29, 1995. The others now live in Houston.

Jerry Leal married Juanita Murphy and they have two children: Camille, born in 1968 and Samuel Waddy, born in 1971. Jerry and Juanita were divorced, and in 1987 he was living in Abilene, Texas. He died January 6, 1993, in Houston.

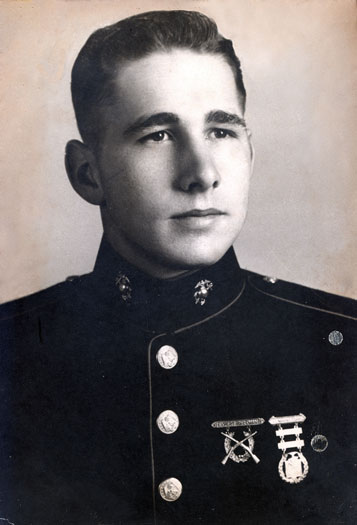

Bryan Cahill Munson

Bryan Cahill Munson was a freshman at Texas A. & M. College when he joined the U. S. Marine Corps. He volunteered so that he could be a marine rather than be drafted into the army. He could have stayed out of combat service entirely because he had a severe ankle injury when he was a child and retained a slight limp all of his life. He felt that it was his duty to defend and fight for his country. He was six feet four inches tall, played football, won medals as an excellent swimmer and as an expert rifleman, and was an accomplished horseman. Horses and ranching were the love of his life, and he was also “the apple of his father’s eye.”

Bryan was very proud of being a Seagoing Marine and was assigned as an orderly to Admiral Raymond Spruance aboard his flagship, the heavy cruiser Indianapolis. The cruiser fought valiantly in several seas. As part of the Fifth and Third Fleets of Spruance and Admiral William Halsey, she raced far ahead of the carriers and battleships, screened only by the “cats whiskers" of destroyers.

The U. S. was in the final stages of the war against Japan when, on March 31, 1945, the first landings were to be made on Okinawa. Indianapolis and New Mexico were far forward in fire support when four kamikazes arched down out of a leaden sky. Navy planes got two and New Mexico splashed one. The fourth crashed into the port side of Indianapolis. The bomb tore loose and crashed through several decks, killing nine sailors and wounding twenty. Her number four propeller shaft was damaged. Spruance transferred his flag to New Mexico, and Indianapolis was forced to return at reduced speeds, zig-zagging across the broad Pacific, to Mare Island Naval Shipyard in San Francisco Bay.

Bryan Munson, just 19 years old, was home on leave while his ship was under repair at Mare Island. When Indianapolis was ready, the Navy contacted Munson. The ship was shorthanded for an important mission, but Bryan did not have to report — a Seagoing Marine’s assignment was two years at sea and then two years stateside, war or no war. Bryan had served his two years at sea, but he chose to go back because he was needed. He said that he was “going back and hurry to get this war over with so everybody could come home.” He achieved this goal. His mission did lead to the prompt end of the war, all the soldiers and sailors came home, and Bryan Munson earned the Purple Heart, posthumously.

U.S.S. Indianapolis off Mare Island, 10 July 1945

Indianapolis and Bryan Munson were ready on July 8, 1945. An atomic bomb was exploded at Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16. In Washington, President Truman and a few generals and admirals conferred and a decision was made. The U. S. had completed three atomic bombs and a big, fast ship was needed to carry the other two to Tinian Island, where B-29 bombers would deliver them to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Indianapolis topped off her tanks as strange scientific civilians came aboard and huge, canvas-covered packages were placed on deck. Marines kept close patrol on the cargo and Indianapolis made a high-speed run to Tinian. The mysterious packages were delivered and the cruiser proceeded to Guam.

The port director at Guam ordered her to make a slow run - 15.7 knots - to join Rear Admiral McCormick’s units in Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. Captain Charles Butler McVay III of Indianapolis inquired about a destroyer screen but was denied. The Guam port director notified Admiral McCormick and Leyte Gulf to expect Indianapolis in seventy-four hours. Inconceivably, neither received the information. Slowly Indianapolis cruised flat, hot seas, zig-zagging by day, not by night. What was left of the Japanese fleet was at bases on Honshu and Hokkaido, a thousand miles to the north.

On their second night out, July 29, 1945, moonrise was at 10 p.m. At 11 p.m., Japanese submarine I-58, under the command of Lt. Comdr. Mochitsura (Ike) Hashimoto, made a routine nightly surfacing. Lt. Comdr. Hashimoto could not believe his eyes. Something which appeared to be a battleship was approaching from the east, was not zig-zagging, and would pass south of his position at a distance of 4,500 feet. He couldn’t miss. He waited, then fired six torpedoes. Two hit on the starboard side completely ripping out the side and the bottom of the big cruiser. In fifteen minutes Indianapolis headed for the bottom — 7,200 feet down.

Of the 1,196 men aboard, about 850 got into life rafts alive. For the most part, these were the unlucky ones. One hundred men died the first night from burns. They were dropped off the rafts. The survivors blistered in the tropical sun. They died by twos and threes. No rescue units arrived. Four planes passed, but they kept going. Thirst and burns caused many to jump into the sea. Guam didn’t miss the cruiser — neither did Leyte Gulf. Unbelievably, no one in the Navy missed Indianapolis — no one was expecting her. After five days a Navy plane accidentally sighted an oil slick and spotted the rafts. At midnight, August 2, 1945, ships arrived. They saved 316 men including Captain McVay, but over 880 had died. Bryan Cahill Munson was among them.

On August 6, 1945, “the bomb" was dropped on Hiroshima, and Japan surrendered on August 10. The Navy did not release the news of the loss of Indianapolis until the following week, after Japan had surrendered. In the ecstasy of victory, the news was scarcely noticed. Captain McVay was eventually court-martialled for negligence, and Time magazine called this “the most colossal blunder of the war.” Bryan Cahill Munson was awarded the Purple Heart, posthumously, and also the World War II and the Asian Pacific medals. [1]

Joseph Waddy Munson II died in Houston on May 11, 1951 of a

cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 53, but his daughter, Jennie

Kate, writes, “I truly believe that he died of a broken heart, for

he never accepted my brother’s death. His grief was so great that

until the day he died he never gave up hope that Bryan would be

found.”

____________________

- [1] Information for this story was taken from Munson family files which include two newspaper clippings authored by Jim Bishop (source unrecorded) and a 1958 Newsweek magazine review of the book, Abandon Ship! Death of the U.S.S. Indianapolis, by Richard F Newcomb.