The Munsons of Texas — an American Saga

Chapter Eleven

HENRY WILLIAM AND ANN MUNSON AT OAKLAND PLANTATION 1828-1833

SUMMARY

Henry William and Ann Munson moved their family from the Trinity River to Austin's Colony in what is now Brazoria County, Texas, in 1828. They named their new home Oakland Plantation. While here they had two additional sons: Gerard Brandon and George Poindexter Munson. In 1832 Henry William took part in the Battle of Velasco, often considered the first battle of the Texas Revolution. In 1833, at the age of 40, Henry William Munson died at Oakland Plantation of "the fever."

Stephen F. Austin's first empresario grant was approved by the Mexican Government in Mexico City on April 14, 1823. This allowed him to settle 300 families in an area of South Texas near the Brazos River. It contained no limitation as to territory, except that no colonization could take place within ten leagues (thirty miles) of the Gulf of Mexico, nor was a time fixed in which the colonization had to be completed. In effect this was but an approval of the privileges granted to Moses Austin, Stephen F. Austin's father, under the expiring government of Spain on January 21, 1821. Stephen F. Austin returned to his colony in July of 1823, and soon thereafter Governor Luciano Garcia of the Province of Tejas appointed Felipe Enrique Neri, known in history as the Baron de Bastrop, as commissioner to set apart lands and issue titles to the colonists [1].

In an official order issued on July 26, 1823, the governor gave the name of San Felipe de Austin to the prospective capital of the colony. San Felipe was his own patron saint, and the name Austin was added as a graceful compliment to the empresario and to distinguish the capital from the many towns and haciendas in Mexico with the name San Felipe. Austin selected a site on a bluff overlooking the Brazos River at the Atascosita Crossing (near the present town of Sealy in Austin County) and laid out the town. It grew rapidly and was the political center of the colony (and of most of the Anglo settlements in Texas) until the time of the Texas Revolution in 1836. After that time its importance steadily declined and today the site is only a Texas historical park.

The Baron de Bastrop arrived and entered upon his duties of supervision of surveying, recording of field notes, and preparation of land titles. No titles were issued in 1823, but 272 were granted in 1824. Austin's original quota was being quickly filled just at the time Henry William and Micajah Munson and families were moving to the Trinity River area to each claim a plot of 4,428 acres of free land. The free land may have been the reason they did not join the Austin Colony at that time.

In historical perspective, the rapid success of Austin's colonization, the efficient issuance of titles, and his cooperation with the Mexican authorities are impressive. His calm persistence and lack of antagonism together with his considerable administrative skill and his attention to important details were the necessary ingredients for success. He required applications and reviewed prospective settlers carefully, selecting for character, leadership, and industry. It was greatly to his credit and to the benefit of the State's future that he built a colony of solid citizenry. These first 300 families are remembered in Texas history as the "Old Three Hundred". Under the new Mexican colonization law of March 24, 1825, Austin eventually entered into three additional colonization contracts. The first, dated May 20, 1825, called for settlement of an additional 500 families in his existing colony. The second, dated November 20, 1827, called for settlement of another 100 families on the east side of the Colorado River. Then on July 17, 1828, Austin was granted the unusual permission to settle 300 families on the ten coast leagues theretofore reserved, making a grand total of 1,200 families to be introduced. All contracts were fulfilled with carefully selected settlers.

Munson family tradition tells that Austin notified Henry

William Munson in the summer of 1828 that he had selected a fine

site for him to purchase on "Gulf Prairie" and invited Munson to

come over and inspect it. This land was in Austin's last grant of

"ten coast leagues", in which he reserved well over twelve

leagues (53,000 acres) of the best land for himself. Apparently

Munson and Austin inspected this site together in late August,

because on August 27, 1828, they signed a contract ![]() at the neighboring McNeel homestead. Henry William agreed

to buy 554 acres of rich gulf-prairie land for the price of "one

dollar per English acre, payable one year from the first day of

January next", and to move his family there within four months.

The land straddled the headwaters of Jones Creek just west of the

Brazos River and about eight miles from the Gulf of Mexico. The

general area was called Peach Point because of the many wild

peach trees that bloomed there each spring. The November, 1828,

move was confirmed with a formal certificate

at the neighboring McNeel homestead. Henry William agreed

to buy 554 acres of rich gulf-prairie land for the price of "one

dollar per English acre, payable one year from the first day of

January next", and to move his family there within four months.

The land straddled the headwaters of Jones Creek just west of the

Brazos River and about eight miles from the Gulf of Mexico. The

general area was called Peach Point because of the many wild

peach trees that bloomed there each spring. The November, 1828,

move was confirmed with a formal certificate ![]() in Spanish, signed Estevan F. Austin.

in Spanish, signed Estevan F. Austin.

On this land Henry William and Ann Munson and their nineteen slaves built a successful cotton and cattle plantation. They named their new home Oakland Plantation. It is interesting to note that there had been an Oakland Plantation in the Natchez District and one in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, when Henry William had lived in each place. It is not known at what date the attractive two-story Oakland Plantation home was built. The home was referred to as a mansion in letters written by friends. Years later it was destroyed by fire (one report says in about 1858), but large cisterns still mark its location on the prairie. In the 1840s Oakland became one of the many large sugar plantations in Brazoria County. Collapsed remains of the brick sugar mill and the pit from which the bricks were made are still landmarks today.

The plantation was bounded on one side by the Thomas Westall

plantation and on another by that of David Randon. Its major

money products over the years were cotton, cattle, hogs, sugar,

and molasses, shipped mostly to markets in New Orleans. It was

undoubtedly a nearly self-sufficient plantation for the family

and their slaves, with chickens, hogs, sheep, beef and dairy

cattle, corn, vegetables, and fruit from the plantation —

from the natural surroundings there was an abundance of pecans,

blackberries, fish, oysters, clams, ducks, geese, turkey,

rabbits, squirrel, deer, and other game. Finally, after much

tragedy and hardship, the Munsons had found a fertile and

healthful plantation, and the family thrived. It is interesting

that for the next 160 years, up to this day, none of this land

has left the ownership of the family ![]() .

.

Henry William and Ann Munson's last two sons were born here: Gerard Brandon Munson on September 20, 1829, and George Poindexter Munson on June 4, 1832. Both were named for respected early judges, governors, and leaders of Mississippi who were contemporaries of Henry William Munson when he lived there. This again probably reflects Henry William's personal values. (See Insets 13 and 14 for short biographies of Gerard Brandon and George Poindexter.)

But Henry William's years of success and peace were few. To see his family and his plantation grow and thrive must surely have been the most enjoyable years of this life; but it was to be only a few years before political turmoil heightened between the colonists of Texas and their Mexican government, and tragedy was to strike him at an early age.

Anahuac — The Beginnings of the Texas Revolution

Under the Mexican constitution which went into effect in 1824, the first presidential term was filled by the true patriot Guadalupe Victoria. In the election in September of 1828, it was recorded that Vicente Guerrero received a large majority of the popular vote, but when the electoral college met, Manuel Gomez Pedraza received the vote of ten of the eighteen states' delegates. Before the April, 1829, inauguration, the followers of Guerrero, headed by Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna and Lorenzo de Zavala, fomented a revolution, marched upon the capital, and installed Guerrero as president with an unprincipled military officer, Anastasio Bustamente, as vice-president. Before the end of 1829, Bustamente had led a successful revolution against Guerrero, assumed the presidency, and Guerrero was captured and put to death. Bustamente assumed dictatorial powers and entered upon a highly contentious regime. The measures that he and his government promulgated led directly to the revolution by the Texas colonists and to Mexico's loss of the territory of Texas.

On April 6, 1830, Bustamente issued a decree, passed by the Congress, reversing the existing immigration laws. It included the famous eleventh article which essentially forbade any further immigration of North Americans into Texas. This was clearly a reaction to the increasing American population in Texas and to the fact that in 1825, 1827, and 1829 the United States, through its minister to Mexico, had made efforts to purchase the whole or a part of Texas from Mexico.

Bustamente especially wanted to enforce the thirteenth article of the April decree, which established a customs system and taxes on imports after seven years of duty-free imports. The initial colonization agreement had granted five years of duty-free imports. To enforce this decree he established garrisons and erected forts at various points in Texas. The commanders of these posts were headed by Colonel José de las Piedras with 350 men at Nacogdoches. Juan Davis Bradburn, with 150 men, built and occupied a fort at Anahuac at the mouth of the Trinity River on Galveston Bay. Lieutenant Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea, with 130 men, built and garrisoned a fort at Velasco on the east side of the mouth of the Brazos River. There were also Mexican troops stationed at San Antonio and Goliad, and Fort Teran was established on the Neches River.

To make matters worse, these troops were to be supported by receipts from the custom houses and other taxes levied upon the inhabitants. It approached a replay of "taxation without representation", a policy previously proven not to be the way to handle enlightened colonists in a far-off land. By early 1831 these encampments were in place, and their effect was constant harassment of the colonists, enforced by military power.

Bradburn's actions at Anahuac, especially, were a series of annoyances, indignities, and oppressions to the population. Before the close of 1831 he issued an order closing to the colonists all gulf ports except the one at Anahuac. This action promised to be absolutely ruinous to the settlers in Austin's, Robertson's, and De Witt's colonies, dependent as they were on the mouth of the Brazos and the landings on Matagorda Bay.

The reaction of the colonists, it appears in retrospect, was a model of a calm but firm response. The people of the Brazos, after consultation, chose Dr. Branch T. Archer and George B. McKinstry to proceed to Anahuac, present the colonists position to Bradburn, and demand a revocation of the order. Bradburn first refused the request, but after a few earnest words from Archer indicating that in the event of a refusal an appeal to arms would be made, he changed his mind and the order was rescinded. The ambassadors returned home with the hope that no further oppressions would occur, and a brief period of calm followed.

In 1831 the governor of the Province of Tejas had finally commissioned Francisco Madero to issue titles to the unhappy settlers on and near the Trinity River. Such commissioners were given the authority to organize municipalities where none existed. Madero exercised this authority by organizing the much needed municipality of Libertad (Liberty) with Hugh B. Johnston as Alcalde. The people were gratified at this recognition of their needs, and the Elizabeth Munson grant of 4,428 acres was finalized.

But Bradburn saw in this act a usurpation of his authority, and he arrested and imprisoned Madero, dissolved the new municipality, and appointed a new Ayuntamiento (council) with its seat at Anahuac. Other annoyances by Bradburn and his soldiers were numerous and of almost daily occurrence. By the spring of 1832 these occurrences had spread alarm over the country. During the confrontations that followed, Bradburn arrested and imprisoned a number of the most prominent citizens of the Trinity settlement including William B. Travis, Patrick C. Jack, Samuel T. Allen, and fourteen others. In this alarming state, William H. Jack of San Felipe de Austin visited Bradburn and sought the release of his brother and fellow prisoners, or their transfer for trial to a civil tribunal. Bradburn's only answer was that the prisoners would be sent to Vera Cruz to be tried by a military court.

William H. Jack returned to the Brazos, reported the result of

his mission, and raised his voice for forcible intervention to

rescue his brother and friends. Messengers spread the news over

the country and men hastened to the suggested point of rendezvous

near Liberty in early June of 1832. From Brazoria came John

Austin, Henry S. Brown, William J. Russell, and George B.

McKinstry, all community leaders, with a few other men. John

Austin (no relation to Stephen F. Austin) was then Alcalde

of Brazoria, second in authority in the Austin Colony, and

undoubtedly a friend of the Munsons. When a sufficient number had

assembled, calling themselves Texians ![]() , they

elected Francis W. Johnson as their captain.

, they

elected Francis W. Johnson as their captain.

Family tradition tells that Henry William Munson participated in the confrontations at Anahuac and Velasco, but no known record shows his participation at Anahuac. His wife, at 32 years of age, was expecting their eighth child, and son George Poindexter Munson was born on June 4, 1832.

The Texians immediately proceeded on a march from Liberty toward Anahuac, and along the way they surprised and captured twenty of Bradburn's cavalry. They made their main camp at Turtle Bayou. Arriving at Anahuac the next day, their leaders met with Bradburn to no avail. After two or three days of nervous confrontation, it was agreed that the Texians would return to Turtle Bayou and the two sides would exchange prisoners, which was the primary goal of the Texians. Their Mexican prisoners were released and a commission was sent to receive the Texian prisoners. The next day firing was heard at Anahuac and a command hastened down. Bradburn had refused to honor the agreement and had attacked the commissioners, who had retreated in good order.

Back at Turtle Bayou the command held a mass meeting and adopted the Turtle Bayou Resolutions, the first set of resolutions by the Texians condemning the Mexican government. The Resolutions recited the many tyrannical acts of Bustamente resulting in the subversion of the legal constitution. Santa Anna had, on January 2, 1832, pronounced against Bustamente and in favor of the Constitution of 1824. The Texians pledged support to "the well deserving patriot, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna" [2]. On examining the position of the enemy, it was deemed imprudent to attack without artillery. Captains John Austin, Henry S. Brown, William J. Russell, and George B. McKinstry were sent to Brazoria to secure reinforcements and three pieces of artillery known to be there.

At this point, Colonel Jose de las Piedras, Bradburns's superior at Nacogdoches, approached with about 150 men, having been appealed to by Bradburn for aid. After a full interchange of views during which he was informed of the outrages of Bradburn, and realizing the resolve of the colonists, Piedras agreed to release all of the prisoners, put Bradburn under arrest, and send him out of the country. All of this was done and the armed citizens left for their homes.

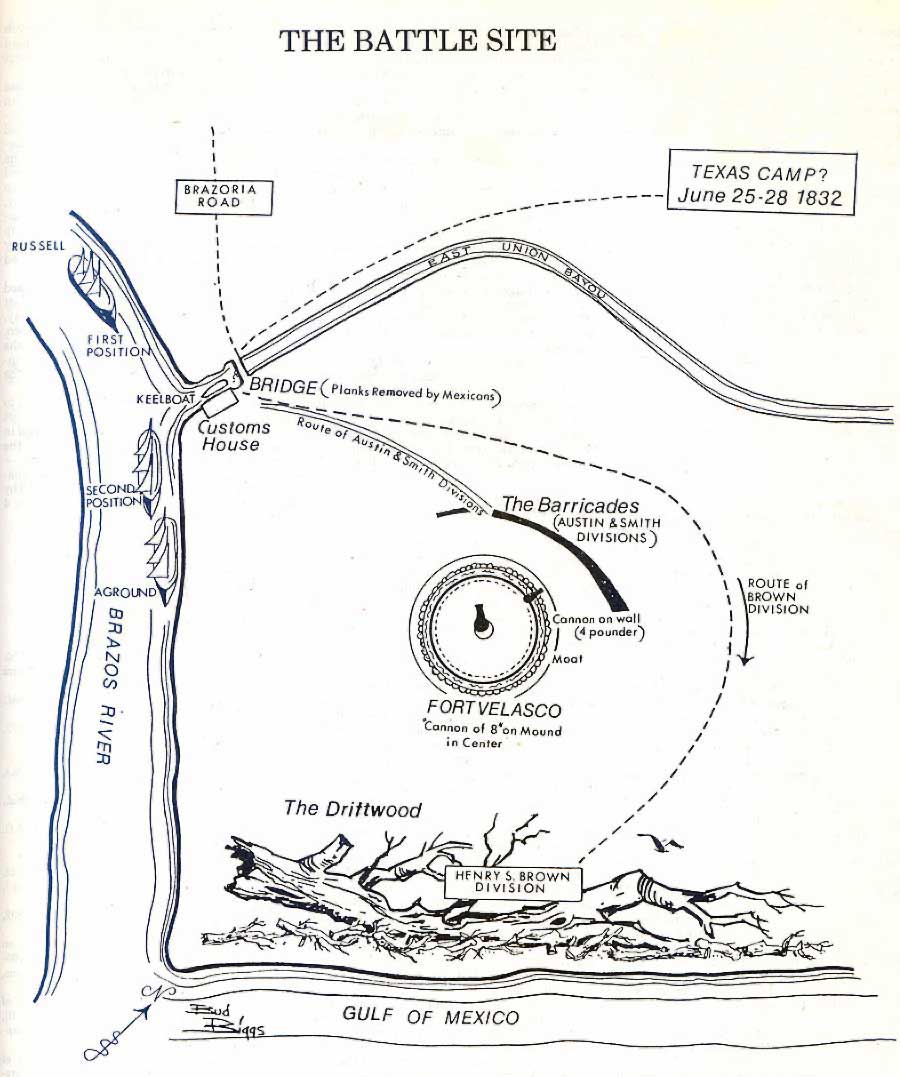

The Battle of Velasco [3]

While the above events were taking place, John Austin, Henry S. Brown, William J. Russell, and George B. McKinstry had reached Brazoria, aroused the people, secured artillery and a naval vessel, and developed a plan to sail for Anahuac by water to gain the release of their countrymen. On June 20, 1832, a meeting was called and approximately one hundred citizens signed "to become a part of the military of Austin's colony and to hold themselves in readiness to march to any point on the shortest notice." A committee of thirteen, which included William H. Wharton, David Randon, Henry William Munson, and Major James P. Caldwell, was appointed to prepare resolutions to "promote the good order and happiness of the colony." After deliberating, this committee reported: ". . .the steps. . .taken were precipitate. . .[and] had at the same time gone so far. . .[that] the only course left for us to pursue was to take up arms and go on with the undertaking. . ." [4]

As they moved down the Brazos River to the gulf, Lieutenant Colonel Ugartechea at Velasco inquired as to their cargo and, on learning that it included two cannon, refused permission for them to pass. This new aspect of the confrontation gave additional grounds for dissatisfaction and brought on the first armed battle between the Texians and the military power of their rulers. These confrontations at Anahuac and Velasco are often considered the first battles — the Lexington and Concord — of the Texas Revolution.

There was a hasty reassemblage of the citizens. Henry William Munson was there, leaving his wife and his three-week-old son. His neighbors, Andrew and James Westall and John and Sterling McNeel, were there. The famous J. Brit Bailey and two of his sons, Smith Bailey and Gaines Bailey, were there; and James P. Caldwell was there. Also present were the future leaders of Brazoria County: William Wharton, Henry Smith, and Edwin Waller. The 112 volunteers were organized into three companies — forty-seven men under John Austin, the senior officer; forty-seven under Henry S. Brown, second in command; and eighteen men in the marines under William J. Russell on the schooner Brazoria. Henry William Munson was with Russell among the marines. James P. Caldwell was in Austin's company.

The fort at Velasco stood about 150 yards from both the river and from the gulf shore. It was built with circular outer walls consisting of rows of posts six feet apart filled between with sand, earth, and shells. Inside these walls was an embankment upon which musketeers could stand and shoot without exposing anything but their heads. In the center was an elevation enclosed by higher posts on which the artillery was placed and protected by bulwarks. Between the fort and the beach was a collection of drift-logs thrown up by the sea.

June 25, 1832, arrived and the battle plan was arranged. Russell, on the schooner Brazoria with two small cannon, a blunderbuss, and eighteen riflemen, was to drop down abreast of the fort after nightfall. Brown, with forty-seven riflemen, was to proceed to the east, then move southwesterly along what is now Surfside Beach and take a position behind the drift-logs. Austin was to approach from the north and take a position within easy range of the fort, each of his men being provided with a portable palisade made of three-inch cypress planks supported by a movable leg. When in position, Brown was to open fire and draw fire from the fort while Austin's men arranged their palisades.

At about midnight an accidental shot by one of Brown's men revealed their presence and the battle began, the guns of the fort sending forth a blaze of light. Brown's men were in a position to avail themselves of the flashes of light from the fort without exposure on their own part, but those under Austin, which included James P. Caldwell, soon realized that their position was untenable. To escape annihilation they took a position immediately under the wall of the fort and could not be seen or reached by the enemy, nor could they see the persons at whom they wished to fire.

The schooner Brazoria, on which Henry W. Munson was stationed, had come immediately abreast of the fort when Russell turned loose his pieces, discharging slugs, lead, chains, scraps of iron, and whatever else they had been able to pick up for the occasion. The contest raged until daybreak, by which time Austin's men had dug pits in the sand for protection. Thereafter the unerring, experienced riflemen of Austin, burrowed as they were in the sand, and of Brown, among the driftwood, did fearful execution to the defenders of the fort, picking off their heads or their hands as they dared to expose them. So accurate was the marksmanship of these frontiersmen that by nine o'clock more than two-thirds of Ugartechea's men were dead or wounded [5].

On the morning of June 26, Austin sounded a call for a parley and demanded the surrender of the fort. Ugartechea asked for but two conditions — that his officers be allowed to retain their side arms and that the survivors of the fort be allowed to peacefully leave the country. These concessions were promptly made and the fort surrendered. The casualties of this first battle were, on the part of the Texians, seven killed and twenty-seven wounded; and on the part of the Mexicans, forty-two dead and seventy wounded — 112 casualties out of 150 combatants (see footnote 5). Crowned with victory, these citizens expected to proceed to the aid of their friends at Anahuac, but hearing of the favorable settlement there, they dispersed and returned to their homes.

One of the injured at Velasco was James P. Caldwell. He returned to Oakland Plantation with his friend, Henry William Munson, where Ann Munson nursed him back to health. From there he proceeded on his way, but the occasion was not forgotten.

Stephen F. Austin and the Beginnings of Brazoria County

The term "Brazoria" was coined by Stephen F. Austin in about

1828. The original name of the Brazos River was Brazos de

Dios (Arms of God), and the early settlers used it as their

main highway of transportation. Among the earliest settlers in

this area were Brit Bailey, Asa G. Mitchell, and Josiah H. Bell.

In 1824 Josiah H. Bell obtained the first land grant along the

Brazos River in this area, and the spot of his settlement became

known as Bell's Landing, though the official name was Marion,

then as Columbia, and today as East Columbia. In 1828 a town was

begun by John Austin about nine miles down river from Bell's

Landing, and Stephen F. Austin gave it the name Brazzoria

because ". . .I know of none [no name] like it in the

world" [6]. In 1832 this area was in

the Mexican Department of Bexar, Jurisdiction of Austin, John

Austin, Alcalde. By July of 1833 it had become the

Jurisdiction of Brazoria, with Henry Smith as Alcalde

![]() . As of

March 1834, all of Austin’s Colony fell within the newly

created Department of the Brazos. The following month the capital

of Brazoria Municipality was moved by popular vote from the town

of Brazoria, Municipality of Brazoria, to Columbia, and the

municipality was renamed Columbia. When counties were created

from the Mexican municipalities by the First Congress of the

Republic of Texas in 1836, Columbia Municipality became Brazoria

County, its current name.

. As of

March 1834, all of Austin’s Colony fell within the newly

created Department of the Brazos. The following month the capital

of Brazoria Municipality was moved by popular vote from the town

of Brazoria, Municipality of Brazoria, to Columbia, and the

municipality was renamed Columbia. When counties were created

from the Mexican municipalities by the First Congress of the

Republic of Texas in 1836, Columbia Municipality became Brazoria

County, its current name.

Stephen F. Austin's sister, Emily, married James Bryan in 1813 in Missouri, where they had three sons: William Joel, Moses Austin, and Guy Morrison Bryan, and a daughter, Mary. James Bryan died in 1822, and Emily then married James F. Perry, and they had three children: Samuel Stephen, Eliza, and Henry Perry. In about 1830 Stephen F. Austin wrote to James F. Perry in Missouri urging him to take Emily and the children to look at land at Peach Point and to meet the Westalls, McNeels, Munsons, Calvits, and Whartons. He wrote, "I mean to make a Little World there of my own. . .We shall all be happy when we are collected at Peach Point" [7]. In 1831 the Perrys moved to Texas, first to San Felipe de Austin, then to a plantation deeded to them by Stephen F. Austin at Chocolate Bayou, and in 1832 to their new home at Peach Point Plantation. In his later years, Austin, who never married, called the Perry plantation his home and spent as much time there as possible. Part of this home and his office still stand there today. When he died in 1836, he was buried in the Peach Point Cemetery beside the grave of his neighbor, Henry William Munson. Years later his grave was moved to the State Capitol in Austin.

The Bryan and the Perry children were raised in the Perry home at Peach Point, and their families have been prominent citizens of Brazoria County for over 150 years [8]. These families have been neighbors and life-long friends of the Munson and Caldwell families up to this day. After the death of James F. Perry, Samuel Stephen Perry became proprietor of Peach Point Plantation and Mordello Munson became his legal and business advisor. Stephen Perry named a son Mordello Perry in honor of Mordello Munson, and Mordello named a son Milam Stephen in honor of Stephen Perry. The Perry descendants still live on the original homestead in Jones Creek, Texas, today.

In 1832 Ann Raney came to Texas from England and remained in Brazoria County for several years. While there she kept a diary which affords much information on the life and people of the times. This is known as Ann Raney's Diary [9]. One excerpt from her diary while she lived with the David Randon family at Peach Point is as follows:

I went to spend the day with Mrs. Munson, a neighbor of Mrs. R [Mrs. Randon, a sister to Sterling McNeel] and an excellent woman. I met with Miss Emeline W [Westall]. . .a young lady who was very good looking and vain in her charms. She was a good girl fond of a romp. Her sister married Mr. G. McN [McNeel]. Emeline was about eighteen years old, quite a pleasant girl. I had met her at the town of Brazoria often before and at many balls and parties. She had been the Belle of the country before our arrival, and it was said quite a favorite with Mr. S. McN. She got into a play with me, and as I was still weak in the lack of strength, I begged her to desist. She replied, "I intend to whip you, Miss R., for taking my beau from me, and I wish you had stayed at Brazoria and not come in our neighborhood." I was nearly exhausted when at last I succeeded in throwing her down, and I sat on her person and paid her up in her own coin by tickling her. She cried, "Let me up Old England, and I will never trouble you any more." I said, "Will you acknowledge you are whipped?" "Yes, yes", she cried, "I am whipped by old England." At this moment whilst we still lay on the floor, and I still sitting on the top of her body, in came Mr. Munson [Henry William] and Mr. S. McN from behind a door in another room, laughing heartily at us both, and having overheard all that passed between us and had seen us fighting. I felt ashamed and left the room to recover my breath which was nearly exhausted. Emeline now ran out of the room also.

The Last Years of Henry William Munson

During his last years, Henry William Munson was a successful

planter and stockman. He acquired additional large tracts of land

![]() —

one on the Bernard River, one between the Brazos River and Oyster

Creek north of Bell's Landing, and another on the Navidad River.

A letter dated February 1, 1833, from a Mr. J. Matthews, stated

that he was unable to pay the note owed to Mr. Munson because his

crop turned out badly, and he asked for an extension. A statement

dated April 11, 1833, from G. Logan listed new plantation

equipment purchased by Mr. H. W. Munson and repairs made to other

plantation machinery. Henry William was also investing money for

the estate of his late brother, Micajah, as there is a list of

notes in the estate of Henry W. Munson with the notation that

they belonged to the estate of Micajah Munson. There is also a

statement signed by S. Whiting indicating that he had received

money due Elizabeth Munson from H. W. Munson.

—

one on the Bernard River, one between the Brazos River and Oyster

Creek north of Bell's Landing, and another on the Navidad River.

A letter dated February 1, 1833, from a Mr. J. Matthews, stated

that he was unable to pay the note owed to Mr. Munson because his

crop turned out badly, and he asked for an extension. A statement

dated April 11, 1833, from G. Logan listed new plantation

equipment purchased by Mr. H. W. Munson and repairs made to other

plantation machinery. Henry William was also investing money for

the estate of his late brother, Micajah, as there is a list of

notes in the estate of Henry W. Munson with the notation that

they belonged to the estate of Micajah Munson. There is also a

statement signed by S. Whiting indicating that he had received

money due Elizabeth Munson from H. W. Munson.

The year 1833 was a year of disaster for the Brazoria area and for the Munsons. It is referred to as "The Year of the Big Cholera". Heavy and continuous spring rains turned the entire gulf coast region into one giant flooded river. Crops were ruined, plantings were impossible, and livestock and wild animals were drowned, their decaying carcasses littering the landscape. The bacteria which causes Asian cholera, Vibrio comma, a frequent visitor to Mexico and the southern United States, thrived in this environment. Cholera is very contagious, causes severe diarrhea and intense vomiting, and the victim often dies within a short time. James A. Creighton, in A Narrative History of Brazoria County, reports of this time: "Health conditions became unbelievable. Velasco was practically depopulated. Brazoria a charnel house with perhaps eighty reported dead." This was the most severe cholera epidemic ever recorded in Texas and Mexico. It was reported that in Mexico City over 10,000 residents died of cholera in the summer and fall of 1833. Brazoria County lost many leading persons to cholera including John Austin and his two children; Thomas, James, and Emeline Westall; two sons of Josiah H. Bell; Dr. C. G. Cox; D. W. Anthony, editor of the only newspaper in Texas; and possibly John McNeel, Mary E. Bryan, Brit Bailey, and Henry William Munson.

Henry William Munson died on October 6, 1833, at Oakland Plantation at the age of 40. The cause of his death, as passed down through family tradition, was yellow fever. In A Narrative History of Brazoria County it is listed as cholera. In discussing this period in his book, Texas, James Michener says of the 1833 cholera epidemic: "Called alternately the plague, or cholera, or the vomiting shakes, or simply the fever. . ." This last term apparently sufficed for a description of either cholera or yellow fever, so we probably shall never know.

A bill for Henry William Munson’s coffin from Haley

& Carson, dated October 8, 1833, gives the cost as $16.00. He

was buried in the Peach Point Cemetery. Family tradition places

the spot beside a huge live oak tree ![]() near the grave of Stephen F. Austin, who died three years later,

in 1836. James P. Caldwell was buried here in 1856. Two state

historical markers

near the grave of Stephen F. Austin, who died three years later,

in 1836. James P. Caldwell was buried here in 1856. Two state

historical markers  at

the entrance to the cemetery tell brief stories of the lives of

Henry William Munson and James P. Caldwell.

at

the entrance to the cemetery tell brief stories of the lives of

Henry William Munson and James P. Caldwell.

Henry William Munson's last words to his wife were, "Educate my children." This request was fulfilled to the fullest, as sons William, Mordello, Gerard, and George were sent first to local private schools and then to secondary schools and colleges in Texas, Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, and Illinois.

Henry William Munson left an estate appraised at $26,825.00 including 9,699 acres of land as follows:

554 acres at Oakland Plantation

2,479 acres bought from Bryan at $3 per acre

2,222 acres in Gray & Moore League

4,444 acres on the Navidad

Mary Austin Holly, writing at the time, referred to Ann Pearce

Munson as "the wealthy widow Munson" [10]; but she was left with a

most difficult situation — alone in a frontier world of

political turmoil with a large plantation, many slaves, and four

young sons: William Benjamin aged 9, Mordello Stephen aged 8,

Gerard Brandon aged 4, and George Poindexter aged one — and

she was but 33 years old.

____________________

- [1] Historical material in this chapter is taken primarily from John Henry Brown, History of Texas; and Eugene C. Barker, The Life of Stephen F. Austin.

- [2] John Henry Brown, History of Texas, Vol. 1, p. 180.

- [3] Material in this section is taken primarily from John Henry Brown, History of Texas.

- [4] Munson Papers, see Appendix 1.

- [5] This version is from John Henry Brown, History of Texas. Many historians are convinced that Brown grossly exaggerated Mexican losses in most encounters. For example, the Handbook of Texas states that in the Battle of Velasco the Mexicans had five dead and sixteen wounded out of a force of between 90 to 200 men. The true results will probably never be known.

- [6] History of Brazoria County, Brazoria County Federation of Women's Clubs, April, 1940.

- [7] Eugene C. Barker, The Austin Papers.

- [8] Marie Beth Jones, Peach Point Plantation, The First 150 Years, Texian Press, Waco, Texas, 1982.

- [9] Munson Papers, see Appendix 1.

- [10] James A. Creighton, A Narrative History of Brazoria County, p. 49.